Peace is wonderful. Reality, not always. The end of the war obviously wasn’t a matter of “See ya,” and bolting, but a complicated business in more ways than one, both in the journey home and what waited when a serviceperson got there. Our fighting forces didn’t all land on foreign soil overnight, and they wouldn’t get home overnight, either.

The mammoth task of bringing our servicepeople home began in May of 1945, and certain logistical standards had to be met.

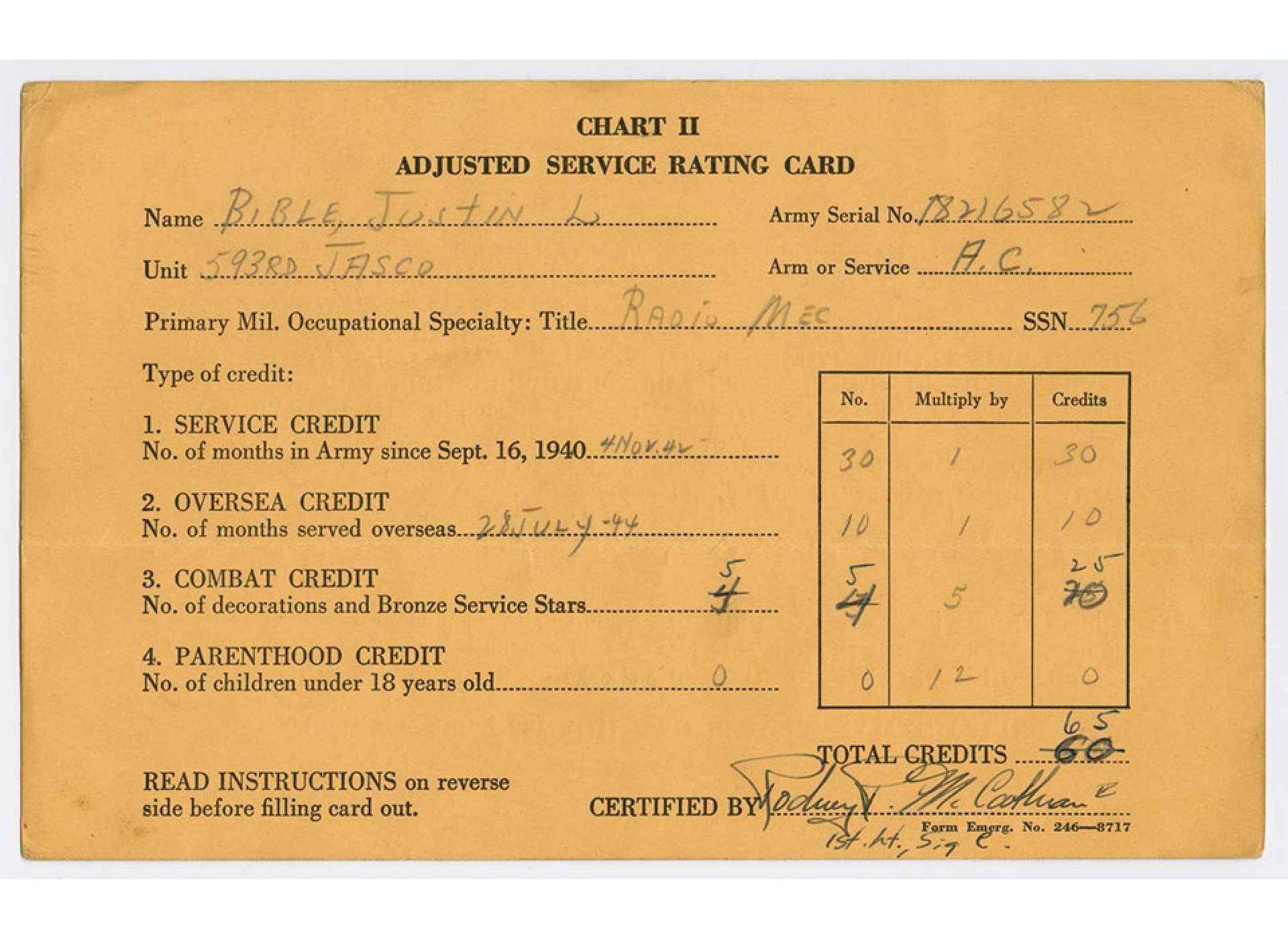

Starting in September of 1944, servicemen and women had to rack up a certain number of points before being mustered out. Each month in the service gave someone a point. Each month spent overseas was another point. Campaigns were five points apiece. A veteran could claim twelve points per dependent for a maximum of thirty-six points. In order to be sent home, a serviceperson had to have at least forty-four points.

After a year the point system was jettisoned because other issues presented themselves. For one thing, the points system was imperfect and too subjective, with men who had been in service longer racking up fewer points than relative newbies who had children before coming over. For another, while demobilization was progressing, there simply weren’t enough conveyances for servicepeople to get home with, and the men overseas were getting bored and restless.

Fortunately, help was on the way in the form of Operation Magic Carpet, which ran from September of 1945 until September of 1946. Almost four hundred sailing vessels of various kinds were used, packed to the gills with bunks, and on average four-hundred fifty thousand solders came home each month. Prisoners of war from Japan and Germany were sent home by Operation Magic Carpet as well. It didn’t matter what kind of ships were in on the operation, either, as both military and civilian ships were pressed into service. Aircraft carriers were the most popular way to get home because they had the widest variety of things to do for fun-starved veterans.

Despite the concerted efforts at repatriation, some servicemen revolted in January of 1946 when demobilization temporarily slowed down. In Manila, thousands of soldiers marched after a transport ship was cancelled. In Tokyo and Japan, Army mailrooms stamped, “No Boats, No Votes” on all outgoing mail. In Paris, soldiers marched waving flares. Eleanor Roosevelt spoke to some of the revolting soldiers when she was on a visit to London, and she looked at their plight with motherly understanding, telling the press that these men needed to be kept busy because boys will be boys. The message in each locale was the same: “We want to go home, so hurry up and get us there.”

Repatriation wasn’t just for the living. America’s dead were also being sent home in an effort that took place between 1947 and 1951 at a cost of one-hundred sixty-three million dollars. In all, sixty percent of America’s dead, or around 171,000 bodies, were brought back to America, although families having the bodies of their World War Two dead repatriated continues to this day.

It wasn’t just a matter of getting back on American soil, either. For those who were convalescing, there were hospital trains, but everyone else had to take whatever was available, which meant planes and trains were extremely crowded as the surge of veterans made their way home, so attaining the dream of going home again was always complicated.

And what was Hollywood up to during this time? Still making movies, of course, and happy the war was over, but like others around the United States and the world, Hollywood and its citizens felt uneasy at what would be next.

The movies of late 1945, while there was plenty of fun going on, seemed to reflect a certain cynicism. Duplicity was a thing, even if it was played in fun. and among the many, many movies featuring some kind of con, Mildred Pierce saw her husband cheat on her with her daughter. A farm girl posed as an opera singer in Hit the Hay. Captain Tugboat Annie saw its title character’s rival tell a lie to replace her in a tugboat fleet. A strict prison warden sees his own son become an inmate in his prison in Within These Walls. Peggy Ryan writes fictitious diary entries in Men In Her Diary. Allotment Wives is about women who scammed their way into marrying multiple servicemen so they could collect their allotments and then the insurance payouts if they were killed (this actually happened, by the way).

Deception is great story fodder, but after a war and a long buildup to that war, it seemed extremely timely, and meanwhile there was the question of what everyone would do once our servicepeople were back from overseas. Getting home was one thing. Starting regular life back up again was quite another. Naturally this gave rise to movies dealing with what awaited the servicepeople coming home, but we’ll get into that next month.

Another post is coming out on Thursday. Thanks for reading, all, and I hope to see you then…

Mildred Pierce (DVD and Blu-ray) and Allotment Wives (streaming only) are available to own from Amazon.

~Purchases made via Amazon Affiliate links found on this site help support Taking Up Room at no extra cost to you.~

If you’re enjoying what you see on Taking Up Room, please subscribe to my Substack page, where you’ll find both free and paid subscriber-only reviews of mostly new and newish movies, documentaries, and shows. I publish every Wednesday and Saturday.

Fascinating post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, John–glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike