When most people think of Alistair Cooke, at least people of my generation and before, we think of the dapper English gentleman on Masterpiece Theatre or Upstairs Downstairs, sitting in the posh wing chair bidding all of us a good evening before introducing that night’s program. Mr. Cooke was an institution, and Masterpiece Theatre hasn’t been the same without him.

What a lot of people may not know is that prior to Cooke’s hosting days, he was a very respected journalist. He studied at Yale and Harvard in the early nineteen thirties and became an American citizen in 1941. Before the war he was primarily known for his dispatches about American life to the BBC, which, in 1946, would become Letters From America.

When America entered the war in 1941, Cooke decided to take a trip around the United States and document how the different states and regions changed and mobilized in response, Armed with a roadster fitted with retreaded tires and an elusive ‘C’ gas coupon, Cooke spent six grueling months on the road, culling his research in a book, The American Home Front, 1941-1942.

Cooke had a way of being around when big things happened, albeit inadvertantly. He was present when Robert F. Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in 1968 and sent a vivid report to Britain of Ethel Kennedy’s shock and horror as she bent over her husband.

On November 15, 1941 he was at La Guardia Airport when Japan’s Special Ambassador Saburo Kurusu touched down on his way to Washington, D.C. Cooke’s major impression of Japan’s purported “messenger of peace” was how tired he looked. He also charitably noted that Kurusu was married to an American, and because of his assignment, had to leave his family while his brother was dying and his daughter was getting married.

One of the great things about Cooke’s book is its immediacy. Cooke effectively paints a picture of Americans enjoying their homes during what we now know as the calm before the storm, if only to emphasize how much of a blindside Pearl Harbor was and how swiftly the nation changed. People went to the movies, had apple pie with ice cream, took naps, and otherwise lived out their weekend.

Then it suddenly all changes. Cooke mentions that Shostakovich’s First Symphony was playing on the radio when the news of Pearl Harbor broke, and that for many people, including him, the horror of the event was dulled by their wondering where Pearl Harbor was. It wasn’t until Roosevelt’s speech the next day that the new reality began to sink in.

After a typically cumbersome process of getting cleared to make the trip, Cooke set out from Washington, D.C. on Februrary 27, 1942, and he covered an immense swath of the United States in a very short amount of time. The detail isn’t exhaustive, but it’s very full and deeply focused. Ergo, we may see details that might be uncomfortable today, such as a wildly exaggerated caricature of a Japanese soldier on the cover of a magazine. Cooke doesn’t give an opinion one way or the other when these kinds of things pop up; he tends to stay matter-of-fact and let the reader draw their own conclusions.

That’s par for the course with the trip. Cooke doesn’t do a lot of editorializing beyond describing what he sees, and he sees a lot. He describes how America went from having a fighting force the size of Sweden’s to seeing servicepeople literally everywhere. He goes into detail about glycerin production and how peanuts were highly prized, as were soybeans, because the fat was used to make explosives. Farmers who were making basically nothing during the Depression were suddenly making huge profits.

Cooke covers the darker side of the home front, too. An aspect of World War Two that isn’t often talked about today is V-girls, with the “V” standing for “Victory.” These women saw the Forces as a meet market and while many of them were simply out for a good time, there were those who tried to take advantage of whomever they could. Cooke mentions one woman who married seven soldiers under assumed names. Until she was found out, she was not only drawing seven different allotment checks, but if any of her sham husbands were killed, she would draw their insurance payouts as well. Army Air Force pilots were especially vulnerable to these kinds of schemes because their training was short and their chances of getting killed were high.

For me, the section on California was absolute gold, since my parents and grandparents on both sides lived in the southern half of the state during the war. Cooke mentions the unavoidability of owning a car in California because of the sheer size of the place, which is still true, thank you very much. He also mentions Imperial Valley, where my mom was born in November of 1941, and how it was one of the most heavily-fortified areas of the country because of its prolific agricultural output (On a side note, my grandpa was never drafted because he was married and a farmer, which gave him protected status).

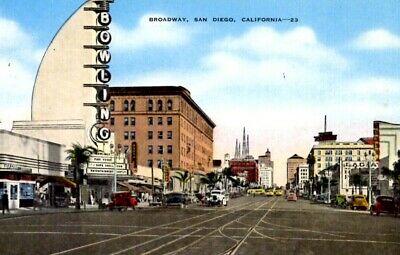

Cooke goes into even more detail about San Diego, where my dad was born three months after Pearl Harbor. In the first six months of 1942 the city’s population increased by fifty percent due to the influx of Navy personnel, and the problem was so bad military families were being housed in multi-purpose rooms in schools. There was tremendous pressure on families already living in San Diego to either house someone or help people out in some way. Naturally, moving around the city was a chaotic business.

Manzanar was another place Cooke visited, and he presents a very stark picture of the camp: windowless, heatless tarpaper dormitories divided by partitions. The people who were brought to these places came from all sorts of occupations and spent their time making the best of a very bad situation. While Southern Californians’ opinions on Japanese Americans ran the gamut, they still made an effort to help the Japanese establish amenities at the camp.

Cooke was clearly uncomfortable with Americans being interned, and summed his visit up thusly: “I drove away from Manzanar none too proud of the showing we had made in running the first compulsory migration of American citizens in American history–not counting the Indians.”

During the rest of the trip, Cooke met factory workers and saw places where one would never know there was a war going on, such as the road from Pasadena to San Francisco. He never ceased to be amazed by America’s vast diversity.

Unfortunately, by the time Cooke was ready to publish his travelogue, the war was winding down and his publisher reneged. No one wanted to read about the war once it was over; everyone was in too big a hurry to forget. Cooke’s manuscript languished for sixty years in the back of a closet, not to be disturbed until his secretary found it during a clear-out a few weeks before Cooke died. The book would finally be published in 2006.

While Cooke’s book is a pleasure to read, it can be slightly dry at times, particularly toward the end, because his fatigue seemed to be showing. However, these bits are few and far between because the material is so compelling. It’s not an exaggeration to say that what Cooke captured in these pages can never be duplicated, simply because no one else saw what he saw in the way he saw it in the moment that he saw it. That makes The American Home Front truly unique.

Another review is coming up on Friday. Thanks for reading, all…

~Purchases made via Amazon Affiliate links found on this site help support Taking Up Room at no extra cost to you.~

Works Cited

Cooke, Alistair. The American Home Front, 1941-1942. New York City: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006.

One thought on “Reading Rarities: The American Home Front, 1941-1942”